Cultural revolution. Exam. story. briefly. cultural revolution in the USSR Results of the cultural revolution 1920 1930

The class approach to culture was primarily reflected in the activities of Proletkult. This is a mass organization that united more than half a million people, of which 80 thousand worked in the studios. Proletkult published about 20 magazines and had branches abroad. The task was put forward of creating an independent proletarian culture, free from any “class impurities” and “layers of the past.” Proletcult concepts denied the classical cultural heritage, with the exception, perhaps, of those artistic works in which a connection was revealed with the national liberation movement. Decisive steps in continuing the mistakes of Proletkult were taken in October 1920, when the All-Russian Congress of Proletkults adopted a resolution that rejected incorrect and harmful attempts to invent a special, proletarian culture. The main direction in the work of proletarian organizations was recognized as participation in the cause of public education based on Marxism. A very influential creative group was RAPP (Russian Association of Proletarian Writers). Calling for a struggle for high artistic excellence, polemicizing with the theorists of Proletkult, RAPP at the same time remained from the point of view of proletarian culture. In 1932, RAPP was dissolved. The artistic life of the country in the first years of Soviet power is striking in its diversity and abundance of literary and artistic groups. In April 1932, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks adopted a resolution “On the restructuring of literary and artistic organizations,” which provided for their dissolution and the creation of unified creative unions. In August 1934, the Writers' Union of the USSR was formed. The very first congress ordered workers of Soviet art to use exclusively the method of socialist realism, the principles of which are party membership, communist ideology, nationality, and “the depiction of reality in its revolutionary development.” Along with the Writers' Union, the Union of Artists, the Union of Composers, etc. later emerged. To guide and control artistic creativity, the Government established a Committee on Arts.

Thus, the Bolshevik Party completely placed Soviet literature and art at the service of communist ideology, turning them into a propaganda tool. From now on, they were intended to introduce Marxist-Leninist ideas into the consciousness of people, to convince them of the advantages of a socialist community, of the infallible wisdom of party leaders. Workers of art and literature who met these requirements received large fees, Stalinist and other prizes, dachas, creative trips, trips abroad and other benefits from the Bolshevik leadership.

The fate of those who did not submit to communist dictates was, as a rule, tragic. The most talented representatives of Soviet culture died in concentration camps and the dungeons of the NKVD: The paths of ideological and political self-determination and the life destinies of many people of art did not develop easily during this turning point. For various reasons and in different years, great Russian talents ended up abroad. Many theater groups emerged. The Bolshoi Drama Theater in Leningrad played a major role in the development of theatrical art. The mid-20s saw the emergence of Soviet drama, which had a huge impact on the development of theatrical art. While drama theaters had restructured their repertoire by the end of the first Soviet decade, the classics continued to occupy the main place in the activities of opera and ballet groups. Soviet sculptors focused on creating monuments depicting V.I. Lenina, I.V. Stalin, other leaders of the party and state. Each city had several monuments to leaders. The sculptural group “Worker and Collective Farm Woman” created by V. Mukhina, depicting two steel giants, was considered a masterpiece of monumental art of that time. Literary and artistic magazines played a major role in the artistic life of the country. New magazines such as “New World”, “Krasnaya Nov”, “Young Guard”, “October”, “Zvezda”, “Print and Revolution” became popular. Many outstanding works of Soviet literature were published for the first time on their pages, critical articles were published, and heated discussions were held. The production of newspapers, magazines, and books has increased. In addition to all-Union and republican newspapers, almost every enterprise, factory, mine, and state farm published its own large-circulation or wall newspaper. Books have been published in more than 100 languages. The radioification of the country took place. Radio broadcasting was carried out by 82 stations in 62 languages. There were 4 million radio points in the country. A network of libraries and museums developed. During this period, social scientists who advocated the preservation of the new economic policy were subjected to repression. Thus, prominent Russian economists A.V. were arrested and subsequently shot. Chayanov and N.D. Kondratiev. Cultural ties with foreign countries developed. The membership of the Russian Academy of Sciences in international organizations was renewed. Domestic scientists participated in international conferences and foreign scientific expeditions. However, the strengthening of the command-administrative system and tightening of control led to a narrowing of the volume of information coming from abroad.

Personal contacts with foreigners and stays abroad became grounds for undeserved accusations of espionage against Soviet citizens.

Control over the travel of scientists and cultural representatives abroad was tightened. A huge amount of work has been done to eliminate illiteracy. On the eve of the October Revolution, about 68% of the adult population could not read or write. The situation in the villages was especially bleak, where about 80% were illiterate, and in national regions the share of illiterate people reached 99.5%. On December 26, 1919, the Council of People's Commissars adopted a decree “On the elimination of illiteracy among the population of the RSFSR,” according to which the entire population from 8 to 50 years old was obliged to learn to read and write in their native or Russian language. The decree provided for a reduction in the working day for students while maintaining wages, the organization of registration of illiterate people, the provision of premises for classes for educational clubs, and the construction of new schools. In 1920, the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for the Elimination of Illiteracy was created, which existed until 1930 under the People's Commissariat of Education of the RSFSR. The school experienced enormous financial difficulties, especially in the first years of the New Economic Policy. 90% of schools were transferred from the state budget to the local one. As a temporary measure, in 1922, tuition fees were introduced in cities and towns, which were set depending on the wealth of the family. As the country's economic situation generally improved, government spending on education increased; Patronage assistance from enterprises and institutions to schools has become widespread. All this allowed the state in August 1925 to adopt the decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR “On the introduction of universal primary education in the RSFSR and the construction of a school network.” By the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution, this task was solved in a number of regions. According to the 1926 census, the proportion of the literate population doubled compared to pre-revolutionary times and amounted to 60.9%. There remained a noticeable gap in literacy levels between city and village - 85 and 55% and between men and women - 77.1 and 46.4%. Increasing the educational level of the population had a direct impact on the process of democratization of higher education. The Decree of the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR dated August 2, 1918 “On the rules of admission to higher educational institutions of the RSFSR” declared that everyone who had reached the age of 16, regardless of citizenship and nationality, gender and religion, was admitted to universities without exams, and was not required to provide a document on secondary education.

Priority in enrollment was given to workers and the poorest peasantry. In addition, starting from 1919, workers' faculties began to be created in the country. At the end of the recovery period, graduates of workers' faculties made up half of the students admitted to universities. By 1927, the network of higher educational institutions and technical schools of the RSFSR included 90 universities (in 1914 - 72 universities) and 672 technical schools (in 1914 - 297 technical schools). By 1930, capital allocations for the school had increased more than 10 times compared to 1925/26. During this period, almost 40 thousand schools were opened. On July 25, 1930, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks adopted a resolution “On universal compulsory primary education,” which was introduced for children 8-10 years old in the amount of 4 grades. By the end of the 30s, the difficult legacy of tsarism - mass illiteracy - was overcome. According to the 1939 census, the percentage of literate people aged 9-49 years in the RSFSR was 89.7%. The differences between urban and rural areas and between men and women in literacy levels remained insignificant. Thus, the literacy rate of men was 96%, of women - 83.9%, of the urban population - 94.9%, of the rural population - 86.7%. However, there were still many illiterates among the population over 50 years of age. By the end of the 30s, there were more than 10 million specialists in the USSR, including about 900 thousand people with higher education. There were twice as many engineers with higher education as in the United States. However, their level of qualification remained significantly lower. In the 30s, Soviet science switched to a planned system. Many scientific institutions arose on the periphery. Branches of the Academy of Sciences were created in the Transcaucasian republics, the Urals, the Far East, and Kazakhstan. The party demanded that science serve the practice of socialist construction, have a direct impact on production, and contribute to the strengthening of the country's military power. A serious breakthrough was made by Soviet physicists in the field of studying the atomic nucleus. Scientists' research contributed to the creation of future Soviet atomic weapons and nuclear power plants. The culture of the USSR followed its own special path, largely determined by the Communist Party.

Cultural Revolution (1917-1928)

October 1917 is considered the beginning of a new period in the history of Russian culture, although the consequences of the political revolution did not immediately manifest themselves in the cultural life of society.

A distinctive feature of the Soviet period of cultural history is the large role of the party and state in its development. The Communist Party, through a system of state and public organizations, directs the development of public education, cultural and educational work, literature, art, and carries out work on the ideological and political education of the people in the spirit of Marxist-Leninist ideology. The state finances all branches of culture and takes care of expanding their material base. Starting from the first five-year plan, cultural construction is planned throughout the country. Cultural issues occupy a significant place in the activities of trade unions and the Komsomol.

During the years of socialist construction, Marxist-Leninist ideology became established in Soviet society. Mass illiteracy was eliminated and a high level of education was ensured for the entire population.

The struggle for the establishment of Marxist ideology required, first of all, the organization of socialist forces. in 1918 The Socialist Academy was opened, whose main task was to develop current problems of the theory of Marxism, in 1919. Communist University named after Ya. M. Sverdlova for propaganda of communist ideas and training of ideological workers.

The formation of Marxist social science was closely connected with the restructuring of the teaching of social sciences at universities and colleges. It began in 1921, when a decree of the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR adopted a new charter for higher education, eliminating its autonomy.

With the victory of the socialist revolution, the essence of the relationship between the state and religious organizations radically changed. The separation of church from state and school from church (decree of the Council of People's Commissars of January 23, 1918), and the widespread deployment of atheistic propaganda among the population contributed to the liberation of culture from the influence of the church. The main task of the party was to promote “the actual liberation of the working masses from religious prejudices...”. Lenin named religion among the main manifestations of the survivals, remnants of serfdom in Russia.

Communist scientists united in societies for the scientific development, popularization and propaganda of Marxism-Leninism: in 1924-1925. The Society of Militant Materialists, the Petrograd Scientific Society of Marxists, and the Society of Marxist Historians were created.

With the general improvement of the country's economic situation since 1923. a pearl began in school construction. The growth of government investments, patronage assistance from enterprises and institutions, and assistance from the rural population made it possible to begin the transition to universal primary education. the need for this was dictated by the needs of the country. which completed the restoration of the national economy and stood on the threshold of the socialist revolution. In August, the bull adopted the decree “On the introduction of universal primary education in the RSFSR and the construction of a school network.” According to the 1926 population census. The number of literate people in the republic has doubled compared to pre-revolutionary times. The workers' faculties opened in 1919 continued to function. countrywide.

The media were used for the cultural and political education of the people. Along with the periodical press, radio broadcasting became increasingly widespread. On the occasion of the 10th anniversary of Soviet power, a radio station named after Comintern is the most powerful radio station in Europe at the moment. Monumental propaganda became a new form of political-educational and cultural-educational work: in accordance with Lenin’s plan, in the first years after the revolution, dozens of monuments to outstanding thinkers and revolutionaries, cultural figures were laid and opened: Marx, Engels, the obelisk of the Soviet Constitution. In the first years of Soviet power, a tradition of mass holidays dedicated to revolutionary dates developed. A lot of work was done to attract workers to the theater, fine arts, and classical music. For this purpose, targeted free performances and concerts, lectures, and free excursions to art galleries were organized.

The relative isolation of art was destroyed, it became more independent from the ideological and political struggle in society. The task arose of creating a new artistic culture that would meet the historical tasks of the working class, which had become dominant, as well as a new multimillion-dollar audience.

One of the most difficult areas of confrontation between bourgeois and proletarian ideologies was literature and art. The artistic life of the country in the first years of Soviet power amazes with the abundance of literary and artistic groups: “Forge” (1920), “Serapion’s Brothers” (1921), Moscow Association of Proletarian Writers - MAPP (1923), Left Front of the Arts - LEF (1922). ), “Pass” (1923), Russian Association of Proletarian Writers - RAPP (1925), etc. The Soviet state took measures to protect the people from harmful ideological influences and to prevent the release of works of an anti-Soviet, religious, pornographic or hostile nature to any nationality.

Many new theater groups arose, usually not long-lasting, because they were most likely built on enthusiasm rather than on a clear ideological and aesthetic platform and did not have a material base. A large role in the development of Soviet theatrical art was played by the theaters created in those years - the Bolshoi Drama Theater in Leningrad, whose first artistic director was A. Blok, Theater named after. Sun. Meyerhold, Moscow Theater named after. Mossovet. The beginning of a professional theater for children dates back to this time, at the origins of which was N. I. Sats.

Well-known figures in the artistic life of the republic in the first Soviet decade were those writers and artists whose creative activity began and was recognized even before the revolution: V.V. Mayakovsky, S.A. Yesenin, D. Bedny, M. Gorky, K.S. Stanislavsky, A. Ya. Tairov, B. M. Kustodiev, K. S. Petrov-Vodkin. These names personified the continuity in the development of Russian artistic culture, its richness, diversity of styles and trends. M. Gorky occupied a special place in this galaxy. On his initiative, the publishing house “World Literature” was created with the goal of widely publishing the classics of world literature for the people.

The first clues to understanding the revolution that took place relate to its first months and years. These are poems by Mayakovsky, Blok’s poem “The Twelve”, posters by D. Moore, paintings by A. A. Rylov “In the Blue Expanse”, K. F. Yuon “New Planet”, K. S. Petrov-Vodkin “1918 in Petrograd” .

The new revolutionary reality required a new method of its implementation. Conventionally, we can distinguish two main trends in the artistic culture of that time: one searched in the direction of post-revolutionary realistic art, the other connected socialist art with new forms. There was a sharp struggle between supporters of the “formal school”, Lefists and defenders of the “new realism”. But real artists stood above group isolation; there was a process of mutual influence and mutual enrichment of various trends in artistic culture.

Literary and artistic magazines played a major role in the artistic life of the republic. In the 20s, a certain type of Soviet periodical was formed, continuing the traditions of domestic journalism. New magazines such as “New World”, “Krasnaya Nov”, “Young Guard”, “October” became popular. "Star", "Print and Revolution". Outstanding works of Soviet literature were published for the first time on their pages, critical articles were published, and heated discussions were held.

The best works of that time were created outside the framework of any one direction. The classics of Soviet literature included poems and lyrics by V. Mayakovsky, who was a member of the LEF, S. Yesenin, who was associated with the Imagists, and the novel “Chapaev” by D. Furmanov, one of the organizers of the proletarian literary movement.

The mid-20s saw the emergence of Soviet drama, which had a huge impact on the development of theatrical art. Major events of the theater seasons 1925 - 1927 steel "Storm" by V. Bill-Belotserkovsky at the Theater. MGSPS, “Yarovaya Love” by K. Trenev at the Maly Theater, “Fracture” by B. Lavrenev, at the Theater. Vakhtangov and Bolshoi Drama. Classics occupied a strong place in the repertoire. Attempts at a new interpretation of it were made both by academic theaters (A. Ostrovsky’s Warm Heart at the Moscow Art Theater) and by the “left” (A. Ostrovsky’s Forest and N. Gogol’s The Inspector General at the Meyerhold Theater).

The leading creative processes in the fine arts of the 20s were reflected in the activities of such groups as AHRR (Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia), OST (Society of Easel Artists), “4 Arts” and OMH (Society of Moscow Artists). The artists who were members of the AHRR sought to reflect modern reality in forms accessible to the perception of the general public: “The Delegate” by G. Ryazhsky, “Meeting of the Village Cell” by E. Cheptsov, the famous “Tachanka” by M. Grekov. The OST group set itself the task of embodying in images the relationship between man and modern production: “Defense of Petrograd” by A. Deineka, “Heavy Industry” by Y. Pimenov, “The Ball Flew Away” by S. Luchishkin.

While drama theaters had restructured their repertoire by the end of the first Soviet decade, the classics continued to occupy the main place in the activities of opera and ballet groups. The preservation and popularization of Russian musical classics was the leading direction in the work of musical theaters and orchestras, which developed despite the resistance of some musicians' associations. The most important means of propaganda and cultural work among the masses was cinema. Outstanding masters of Soviet cinema, whose work developed in the 20s, were Dziga Vetrov, who opened a new direction in documentary cinema associated with the artistic interpretation of true facts, S. M. Eisenstein - the author of "Battleship Potemkin", "October", which laid the foundation revolutionary themes in an artistic way.

Cultural life in the USSR in the 20s - 30s.

The struggle for the establishment of Marxist-Leninist ideology in the minds of people and in science was the leading direction of the ideological life of society. At the same time, the party's demands on social scientists became stricter: those of them who doubted the absolute correctness of the chosen methods of socialist construction, proposed preserving the principles of the new economic system, and warned about the danger of forced collectivization were removed from work. The fates of many scientists were tragic. Thus, prominent Russian economists A.V. Chyanov and N.D. Kondratyev were arrested and subsequently shot.

In the early 1930s, signs of Stalin's personality cult began to appear in ideological work.

At the turn of the 20s and 30s, new trends emerged in the literary and artistic life of Soviet society. Political disagreements among the artistic intelligentsia are a thing of the past; the majority of writers and artists accepted the new social system as historically conditioned and historically established for Russia. In literature and art, a turn towards realism and a desire for organizational unity were indicated. In 1925 The Federation of Soviet Writers was created. Proletarian organizations carried out great cultural and ideological work in the working environment and contributed to the promotion of talent. The state policy in the field of literature and art in the new conditions was determined in the resolution of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks of April 23, 1923. “On the restructuring of literary and artistic organizations”, it was decided to liquidate the association of proletarian writers and “... unite all writers who support the platform of Soviet power and strive to participate in socialist construction into a single union of Soviet writers with the communist faction in it...”.

The leading theme in the literature of the 30s was the theme of revolution and socialist construction. The inevitable collapse of the old world, the approach of revolution is the main idea of M. Gorky’s novel “The Life of Klim Samgin” (1925 – 1936). The problem of man in the revolution, his fate - this is what M. Sholokhov’s epic novel “Quiet Don” (1928-1940) is about. The symbol of heroism and moral purity became the image of Pavel Korchagin, the hero of N. Ostrovsky’s novel “How the Steel Was Sworn” (1934). The theme of the country's industrial development was revealed in the works of L. Leonov “Sot” and M. Shaginyan “Hydrocentral”. A significant place in the fiction of the 30s was occupied by works dedicated to Russian history and outstanding cultural figures of the past. These are “Peter the Great” by A. Tolstoy, dramas by M. Bulgakov “The Cabal of the Saint” (“Molière”) and “The Last Days” (“Pushkin”). A. Akhmatova, O. Mandelstam, B. Pasternak created brilliant examples of poetry in their work. M. Zoshchenko, I. Ilf and E. Petrov successfully worked in the genre of satire. The works of S. Marshak, A. Gaidar, K. Chukovsky, B. Zhitkov became classics of Soviet children's literature.

Since the late 20s, Soviet plays have established themselves on theater stages. Changes in the repertoire, meetings with workers at public screenings and discussions contributed to bringing the theater closer to life. For the 20th anniversary of the Great October Revolution, the image of V.I. Lenin was embodied on stage for the first time. In the performance of the Theater. Vakhtangov “Man with a Gun” based on the play by N. Pogodin. Among the theatrical premieres of the 30s, the history of the Soviet theater included “The Optimistic Comedy” by V. Vishnevsky, staged at the Chamber Theater under the direction of A. Ya. Tairov, “Anna Karenina” - staged by V. I. Nemirovich-Danchenko and V. G. Stakhanovsky at the Moscow Art Theater.

In 1936 The title of People's Artist of the USSR was approved. The first to receive it were K. S. Stanislavsky, V. I. Nemirovich-Danchenko, V. I. Kachalov, B. V. Shchukin, I. M. Moskvin.

Soviet cinematography took significant steps in its development in the 1930s. At the end of the 20s, its own cinematography base was created: new equipped film studios and cinemas equipped with domestic projectors were created, film production was established, and sound film equipment systems were created. Soviet silent films gradually replaced foreign films from the screen. The rise in popularity of cinema was facilitated by the emergence of Soviet sound films, the first of which were in 1931. “A Journey in Life” (director N. Eck), “Alone” (directors G. Kozintsev and L. Trauberg), “Golden Mountains” (director S. Yutkevich). The best Soviet films of the 30s told about their contemporaries (“Seven Braves”, “Komsomolsk” by S. Gerasimov), about the events of the revolution and civil war (“Chapaev” by S. and G. Vasilyev, “We are from Kronstadt” by E. Dzigan, “Baltic Deputy” by I. Kheifits)

The musical life of the country in those years is associated with the names of S. Prokofiev, D. Shostokovich, A. Khchaturyan, T. Khrennikov, D. Kabalevsky, I. Dunaevsky. Musical ensembles were created that later glorified Soviet musical culture: the Quartet named after. Beethoven, Big State Symphony Orchestra, State Philharmonic Orchestra, etc. In 1932. The Union of Composers of the USSR was formed.

The process of uniting creative forces also took place in the fine arts. In 1931 The Russian Association of Proletarian Artists (RAPH) arose, designed to unite the artistic forces of the country, but it was unable to cope with the tasks assigned to it, and a year later it was dissolved. The formation of artist unions began, uniting artists from the republics and regions.

The transition to socialist reconstruction of the national economy required an increase in the education and culture of the working people. Decisive successes in the struggle for literacy were achieved during the years of the first five-year plan, when universal compulsory primary education for children aged 8–10 years was introduced for 4 years; for teenagers who have not completed primary education - in the amount of accelerated 1-2 year courses. For children who received primary education (graduated from the first level of school), in industrial cities, factory districts and workers' settlements, compulsory education at a seven-year school was established. The implementation of universal education posed complex challenges. it was necessary to strengthen the material base of public education - build new schools, provide students with textbooks and writing materials. There was an acute shortage of teaching staff. The state made large investments, which made it possible to begin the construction of new schools during the first and second five-year plans (during this period, almost 40 thousand new schools were opened). The training of teaching staff was expanded, largely due to the mobilization of communists and Komsomol members to study at pedagogical universities. Teachers and other school employees received increased salaries, which began to depend on education and length of service.

A wide network of various evening schools, courses, and clubs operated in the country, which covered millions of workers and collective farmers. High political activity, consciousness, and initiative in work stimulated the desire of workers for education and culture.

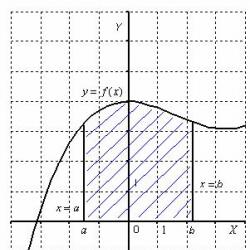

The main goal of the cultural transformations carried out by the Bolsheviks in the 1920s and 1930s was the subordination of science and art to Marxist ideology. Culture was placed under the control of the state, which sought to guide the spiritual life of society and educate its members in the spirit of the dominant ideology.

1) Enlightenment

The first People's Commissar of Education of the RSFSR was A.V. Lunacharsky (1917-1929) 1919 - decree “On the Elimination of Illiteracy”, according to which the population from 8 to 50 years old was obliged to learn to read and write - educational program

A unified state system of public education was created, and a Soviet school of several levels arose. In the 1st Five-Year Plan, compulsory four-year education was introduced, and in the 2nd Five-Year Plan, seven-year education was introduced. Universities and technical schools were opened, workers' faculties (faculties for preparing workers for entry into higher and secondary educational institutions) operated. The training was ideological in nature. A new, Soviet intelligentsia was formed, but the Bolshevik government treated the old intelligentsia with suspicion. In the first years of Soviet power, an innovative school operated: there were no desks, the abolition of the lesson system, homework, textbooks, exams, and grades.

May 1934 - decree on the structure of the educational school: the introduction of primary, junior high and secondary schools.

The educational role of the school is strengthened: the student is obliged to honor the leader and expose the enemies of the people, even if they are members of his family.

The policy of the Soviet leadership in the field of culture in the 20-30s. got the name cultural revolution.

Target:

Raising the cultural level of the people

Strengthening Marxism-Leninism as the ideological basis of social life

Results:

Literacy eradication

Compulsory seven-year education

Opening of 20 thousand schools

Introduction of Marxist ideas into the education system

Repression against unwanted teachers and students.

2) Science

Attracting the old intelligentsia who did not support the Bolsheviks, but saw their duty in working for the country: N. Zhukovsky (aviator), V. Vernadsky (biochemist), N. Zelinsky (chemist), K. Tsiolkovsky (founder of astronautics), I. Pavlov ( physiologist), K. Timiryazev (botanist), I. Michurin (biologist-breeder).

Advances in natural sciences: S. Vavilov (optics), N. Vavilov (genetics and selection), S. Lebedev (production of synthetic rubber), I. Kurchatov (research of the atomic nucleus), P. Kapitsa (physics of low temperatures and strong magnetic fields ), P. Florensky (mathematics), A. Chizhevsky (historiometry, heliobiology).

In the 30s. Stalin declared that all sciences are political in nature. Persecution began against genetics, sociology, and psychoanalysis, which led to the curtailment of their developments in the USSR. History began to be used to educate the people, developing the ideas of Soviet patriotism.

In the fall of 1922, 160 leading scientists, philosophers, historians, and economists who did not share the ideological principles of Bolshevism were expelled from Russia. The dominance of Bolshevik ideology was also asserted in anti-church propaganda, the destruction of churches, and the looting of church property. Patriarch Tikhon, elected in November 1917 by the Local Council, was arrested. Repressed were agricultural scientists N.D. Kondratyev, A.V. Chayanov, philosopher P.A. Florensky, the leading biologist-geneticist N.M. Vavilov, writers O.E. Mandelstam, A.B. Babel, B.A. Pilnyak, actor and director V. E. Meyerhold and many others. Aircraft designers A. N. Tupolev, N. N. Polikarpov, physicist L. D. Landau, one of the founders of the aerodynamic institute S. P. Korolev and others were arrested. The latter worked in the so-called. "Sharashkah" (design bureaus and laboratories in places of detention).

The main reference point in socio-political research was the book published in 1938. A short course on the history of the CPSU(b))" edited by I.V. Stalin.

3) Literature

Some cultural figures ended up in exile: I. Bunin, A. Kuprin, K. Balmont (among non-literators: M. Chagall, I. Repin, S. Prokofiev, S. Rachmaninov, F. Chaliapin, etc.)

A. Akhmatova, O. Mandelstam, M. Prishvin, N. Gumilyov remained in their homeland.

In literature and art, the method “ socialist realism"(a depiction of reality not as it is, but as it should be from the point of view of the interests of the struggle for socialism), glorification of the party, its leaders, the heroics of the revolution. Among the writers, A. N. Tolstoy (“Peter the Great”) and A. T. Tvardovsky stood out.

The genre of satire is developing (I. Ilf and E. Petrov “The Golden Calf”, “12 Chairs”), novels and stories about the revolution and the Civil War appear (M. A. Sholokhov (“Quiet Don”), A. A. Fadeev ( Defeat), M. Zoshchenko, D. Furmanov (“Chapaev”), I. Babel (“Cavalry”), K. Trenev (“Lyubov Yarovaya”).

Creative associations of the 20s: Proletkult (advocated the creation of a special proletarian culture, perceived the heritage of the past as unnecessary trash), RAPP (Russian Association of Proletarian Writers), MAPP (Moscow Association of Proletarian Writers)

1932 - creation Writers' Union.

4) Painting

Creation Association of Artists of the Revolution (AHR), developed the tradition of the Itinerants.

The theme of revolution and civil war was developed by A. Deineka, M. Grekov, B. Ioganson

The work was continued by K. Petrov-Vodkin, B. Kustodiev, P. Filonov, K. Malevich, M. Nesterov, P. Konchalovsky and others.

K. Petrov-Vodkin (“Bathing the Red Horse”, “1918 in Petrograd”, “Death of a Commissar”)

K. Yuon (“New Planet”)

Yu. Pimenov (“Give us heavy industry!”)

M. Grekov (“Tachanka”)

5) Music

The largest phenomena in musical life were the works of S. S. Prokofiev (music for the film “Alexander Nevsky”), A. I. Khachaturian (music for the film “Masquerade”), D. D. Shostakovich (opera “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk”, banned in 1936). The songs of I. Dunaevsky, A. Alexandrov, V. Solovyov-Sedoy gained wide popularity.

6) Cinematography.

Cinematography has made a significant step in its development: the films “Chapaev” by S. and G. Vasilyev, “Battleship Potemkin”, “Alexander Nevsky”, “Ivan the Terrible” by S. Eisenstein, the comedies by G. Alexandrov “Jolly Fellows”, “Circus” , film by M. Romm “Lenin in October”, “Lenin in 1918”, I. Pyryev “Pig Farm and Shepherd”.

Dozens of actors are becoming famous (among them M. Zharov, M. Ladynina, L. Orlova, N. Kryuchkov, V. Zeldin, N. Cherkasov)

7) Sculpture.

The most outstanding sculptural work of the 1930s. became the monument to V. Mukhina “Worker and Collective Farm Woman”.

N. Andreev - Obelisk of the Soviet Constitution in Moscow

L. Sherwood - Monument to A. Radishchev

S. Merkurov - monuments to K. Timiryazev and F. Dostoevsky

8) Architecture

Search for new forms and styles: constructivism (strict, logical lines of buildings in which the structure feels)

In Leningrad - A. Gegelo (Gorky Palace of Culture, Big House (NKVD building).

In Moscow - the Vesnin brothers (Palace of Labor project, Likhachev Palace of Culture, building of the Leningradskaya Pravda newspaper), S. Melnikov (Rusakov House of Culture), Alabyan and Simbirtsev (Red Army Theater, resembles a five-pointed star from above)

B. Iofan - residential building on the Embankment (there is a novel of the same name by Yu. Trifonov about Stalin’s repressions)

9) Bolsheviks and the Church

In the 20s the confiscation of church valuables and terror against clergy begins.

To promote atheism, the “Union of Atheists” was created.

Cultural Policy in the 1920s and 1930s.

General:

Recognition of the elimination of illiteracy, the development of schools and education, the formation of a new Soviet intelligentsia as the most important political tasks (the concept of the cultural revolution)

Recognition of culture and art as an important means of educating the masses in the Communist spirit (culture as part of the overall party cause)

The desire of the party and the Soviet state to place culture under strict control

Bringing to the fore the principle of partisanship when evaluating works of art and culture.

| 1920s | 1930s |

| - In school education there is scope for experimentation and innovation (non-evaluative learning, team method, etc.) - The possibility of developing various artistic styles and trends in art - The existence of various creative organizations and associations - State support for proletarian art, organizations built on its principles, separation from them of so-called sympathizers, fellow travelers, etc. | - In school education - restoration of traditional forms of education, condemnation of experiments as an excess. - Establishment of socialist realism as the only official artistic method in art - Creation of unified creative organizations - Creation of unified creative organizations, which accepted all art workers who shared the platform of Soviet power |

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted onhttp://www.allbest.ru/

Posted onhttp://www.allbest.ru/

List of used literature

1. Objective, subjective prerequisites for changes in the spiritual life of society

The history of Russian culture of the Soviet era must be considered taking into account the real contradictions in the social life of those years, in continuity and comparison with the Silver Age. It should be taken into account that during the Soviet period, two cultures opposed in society: the official, Soviet culture, based on the party’s ideological platform, glorifying the achievements of the new social system, and traditional Russian culture, based on the centuries-old spiritual foundations of our society, professing universal human values. The culture of the Russian diaspora, the heiress of the Silver Age, cannot be discounted.

The overthrow of the cultural milestones of the Silver Age by the Bolsheviks in October 1917 was essentially the overthrow of Russia in its traditional and historical understanding. We are still reaping the tragic fruits of the Bolshevik social experiment. M. Gorky wrote in the newspaper “New Life” in March 1918: “Our revolution gave full scope to all the bad and brutal instincts that had accumulated under the lead roof of the monarchy... it threw aside all the intellectual forces of democracy, all the moral energy of the country."

Under the conditions of a one-party system, the atmosphere within the party was projected (directly or indirectly) onto the atmosphere of the entire society; this also concerned the level of his culture and intellectuality. The processes taking place in the party led to a decrease in the intellectual and moral level of the party in accordance with its utopian program goals. However, this party “subsidence” entailed a “subsidence” of the entire spiritual potential of society. The deformations that took place in the party cannot be considered outside the context of society and its culture.

After the victory of the October Revolution, V.I. Lenin put forward a broad program of cultural transformation in Soviet Russia. In 1923, in the article “On Cooperation,” he first introduced the concept of “cultural revolution” into Marxism, considering it an integral part of socialist construction. “For us,” Lenin wrote, “this cultural revolution is now enough to become a completely socialist country.”

At the same time, cultural problems were supposed to be solved using the notorious “cavalry attack” method. Lenin believed that Russia would be able to reach the cultural level of a “civilized state in Europe” in one or two decades and ensure the “educational and cultural uplift of the mass of the population.”

Lenin's approach to solving the problems of cultural transformation in Soviet Russia was characterized by inconsistency and double standards. Thus, in an effort to quickly eliminate the country’s cultural backwardness, Lenin repeatedly emphasized the importance of using progressive foreign experience in the development of culture. “Now capitalism,” he wrote, “has raised culture in general, and the culture of the masses in particular, much, much higher.” Therefore, Lenin called for “to draw good things from abroad with both hands,” “to take everything that is valuable in capitalism, to take all science and culture for yourself.”

But these Leninist calls were of a propaganda nature, because their practical implementation would conflict with the Leninist class theory of “two cultures.”

The transformations in the country's economy, carried out during the first five-year plans, created an objective need to increase the cultural and educational level of the broad masses, to train qualified personnel for all spheres of the national economy. To solve new economic problems it was necessary to master the achievements of scientific and technical thought.

In this regard, the problems of using the experience of old specialists in the process of industrialization of the country, as well as the formation of a new domestic intelligentsia, acquired great importance. In this regard, the importance of those areas of artistic culture that are directly related to increasing the creative activity of the masses and awakening their labor enthusiasm has objectively increased. Thus, the needs of the economy pushed forward the task of implementing the broadest program of cultural transformations.

The formation of the Soviet intelligentsia was considered one of the most important tasks of the cultural revolution in party documents of that time.

At the same time, since the beginning of the 1930s, a further simplification of its principles has emerged in the interpretation of the idea of the “cultural revolution”. The very concept of “cultural revolution” began to be identified with the solution of only certain urgent tasks of cultural construction - the elimination of illiteracy, the increase in the number of schools, and personnel training. The extreme narrowing of the tasks of the cultural revolution resulted from the speeches of Stalin, who in different years interpreted this very concept in different ways.

Of course, without universal primary education, the victory of the “cultural revolution” would have been impossible. But to reduce it to the basics of literacy, to what was taught in parochial schools before the revolution, was, to say the least, stupid. And since at the end of the 1920s Stalin’s statements began to be binding, the cultural revolution in the country took the simplest and most vulgar path.

The repressive policy towards the old intelligentsia caused great harm to the cause of overcoming the country's cultural backwardness, scientific and technical re-equipment of industry, and transformation of the socio-cultural sphere of society's life. Despite its small numbers, it had a significant potential for professional and spiritual culture, which was clearly underestimated during the first five-year plans. All this soon led to a decline in the intellectual level of society.

As a result of such a utilitarian cultural policy during the years of Stalinism, cultural transformations in the USSR were reduced to the achievement of reduced culture and limited education. Suffice it to say that by 1939, 90% of the country's population had education no higher than primary, 8% of workers and about 2% of peasants had a seven-year education.

The USSR Academy of Sciences became the center of scientific thought, and its branches and research institutes were created throughout the country. In the 1930s, academies of sciences emerged in the Union republics.

By the end of the 1930s, there were about 1,800 research institutions in the USSR. The number of scientific workers exceeded 98 thousand. But in 1914 in Russia there were only 289 scientific institutions and only 10 thousand scientific workers.

Soviet scientists in the 20s and 30s achieved great success in the development of many branches of science. I.P. Pavlov enriched world science with valuable research in the field of studying the higher nervous activity of humans and animals. K.E. Tsiolkovsky developed the theory of rocket propulsion, which underlies modern rocket aviation and space flight. His works (“Space Rocket”, 1927, “Space Rocket Trains”, 1929, “Jet Airplane”, 1930) won the priority of the USSR in the development of theoretical problems of space exploration. In 1930, the world's first jet engine running on gasoline and compressed air, designed by F.A., was built. Zander.

Timiryazev's works on plant physiology became a new stage in the development of Darwinism. I.V. Michurin proved the ability to control the development of plant organisms. Research by N.E. Zhukovsky, S.A. Chaplygin, who discovered the law of formation of wing lift, form the basis for the development of modern aviation. Based on the scientific research of Academician S.V. Lebedev, works by A.E. Favorsky, B.V. Byzova and others in the Soviet Union, for the first time in the world, mass production of synthetic rubber and ethyl alcohol was organized. Thanks to the outstanding scientific discoveries of Soviet physicists, the principles of radar were put into practice in the USSR in the 1930s for the first time in the world. D.V. Skobeltsyn developed a method for detecting cosmic rays. Works of Academician A.F. Ioffe laid the foundations of modern semiconductor physics, which plays a primary role in technical progress. Soviet scientists in the 30s made a great contribution to the study of the atomic nucleus: D.V. Ivanenko put forward a theory of the structure of the atomic nucleus from protons and neutrons. N.N. Semenov successfully worked on problems in the theory of chain reactions. A group of geologists led by Academician I.M. Gubkina discovered the richest oil deposits between the Volga and the Urals. Scientists have made a number of major geographical discoveries, especially in the study of the Far North. A great service to science was provided by the 274-day drift on an ice floe near the North Pole, carried out in 1937 by I.D. Papanin, E.T. Krenkel, P.P. Shershov and E.K. Fedorov.

More modest were the achievements of the social sciences, which mainly served the purposes of ideological substantiation of party policy. The desire of the party and state leadership to ensure the spiritual unity of the people around the tasks of modernizing society in conditions of extreme weakness of material incentives led to an increase in the ideological factor.

The role of historical education and historical research, certainly oriented in the required direction, is increasing. Nevertheless, compared to the 20s, which were characterized by a vulgar class, largely cosmopolitan attitude to history (the school of M.N. Pokrovsky and others), a more favorable atmosphere is being created for the increase in historical knowledge. In 1934, the teaching of history at universities was restored, the Historical and Archaeographic Institute was created, in 1933 - the Historical Commission, in 1936, in connection with the liquidation of the Communist Academy and the transfer of its institutions and institutes to the Academy of Sciences, the Institute of History of the USSR Academy of Sciences was formed. In the 1930s, history teaching began in secondary and higher schools.

In 1929, the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences was founded with 12 institutes.

The most significant achievement of science was the introduction of standards, which was facilitated by the transition to the metric system. An all-Union Standardization Committee was created. In terms of the number of approved standards, the USSR by 1928 had overtaken a number of capitalist states, second only to the USA, England and Germany.

spiritual cultural revolution science

3. Restructuring the system of education, literature and art. Results of the Cultural Revolution

The society's literacy activities have taken on a huge scale. During the First Five-Year Plan, the Komsomol organized an all-Union cultural campaign to the countryside with the aim of eliminating illiteracy. A nationwide literacy movement began.

If during the population census in 1920, 54 million illiterates were identified, then according to the 1926 census, literacy of the population was already 51.5%, including in the RSFSR - 55%. Literacy of the urban population was 76.3%, rural - 45.2%. Along with the elimination of illiteracy, the propaganda tasks of consolidating communist ideology among the masses were also solved.

Working people, on their own initiative, built school buildings (especially in the villages) and purchased equipment for them. Collective farmers sowed plots of land (cultivated hectares) in excess of the plan, the harvest from which went to the fund for universal education.

Mass form of training of workers in 1921-1925. became FZU schools. At least 3/4 of the students in these schools were children of workers. Lower and mid-level technical and administrative personnel (foremen, foremen, mechanics) were trained in technical schools, special vocational schools, and short-term courses.

In 1918, tuition fees at universities were abolished and cash scholarships were established for needy students.

In 1919, workers' faculties were created at institutes and universities, where poorly educated workers and peasants were prepared for entering universities in three years. The number of universities grew rapidly.

Millions of workers and peasants and their children now studied at technical schools, institutes, and universities, becoming technicians, engineers, agronomists, teachers, doctors, and scientists.

In the field of higher education, the government pursued a class policy and created favorable conditions for workers and peasants to enter universities. Measures were also taken to radically change training programs at universities and universities, and remove professors and teachers disloyal to the authorities from universities. This caused serious conflicts, strikes, and protests among students and teachers. At the beginning of the 1920s, historical materialism, the history of the proletarian revolution, the history of the Soviet state and law, and the economic policy of the dictatorship of the proletariat were introduced as compulsory subjects. But the situation with professorships was quite difficult; there was a catastrophic shortage of teachers. Moreover, there were between two and three million people living abroad.

The contradictions of economics and politics, the complexity of social processes during the NEP period were clearly reflected in works of literature, art, architecture and theater. The protest of a significant part of the intelligentsia against the October Revolution and the exile of many cultural figures did not stop the development of art, which was given impetus at the beginning of the century.

The dissent of this time is multifaceted, its social base is more complex: here is the culture of the “Silver Age”, and part of the pre-revolutionary and new intelligentsia.

The Russian artistic culture of dissent was in full bloom: A. Blok, A. Bely, I. Bunin, O. Mandelstam, A. Akhmatova, N. Gumilev, V. Korolenko, M. Gorky, V. Kandinsky, M. Chagall, S. Rachmaninov, F. Chaliapin, I. Stravinsky... Some immediately realized that in the new conditions the cultural tradition of Russia would either be crucified or subjugated (I. Bunin “Cursed Days”), others tried to listen to the “music of the revolution,” dooming themselves. to the tragedy of imminent death without the “air of life.”

New creative associations and groups continue to exist and appear, experimenting in ways that are sometimes far from realism.

The presence of these modernist groups and theories in no way infringed or hindered the search for art that stands on opposite aesthetic positions - a realistic depiction of the social aspects of life's realities.

From the second half of the 20s, the massive flow of literary works began to lose their originality, to be filled with identical cliches, plot schemes, and the range of topics was limited. Works appeared that described pictures of the everyday decay of the intelligentsia and youth under the influence of the New Economic Policy: S. Semenov “Natalia Tarkova” (in 2 volumes, 1925-1927); Y. Libedinsky “The Birth of a Hero” (1929), A. Bogdanov “The First Girl” (1928), I. Brazhin “The Jump” (1928). Finally, in the first half of the 20s, satirical novels based on adventure-adventure, social-utopian plots became widespread: V. Kataev “The Island of Erendorf” (1924), “The Embezzlers” (1926), B. Lavrenev “The Collapse of the Republic Itil" (1925), A. Tolstoy's "The Adventures of Nevzorov, or Ibicus" (1924), A. Platonov's "City of Grads" (1927), stories by M. Zoshchenko.

In the second half of the 20s, short stories developed intensively (“The Ancient Path”, 1927, A. Tolstoy; “The Secret of Secrets”, 1927, Vs. Ivanova; “Transvaal”, 1926, Fedina; “Extraordinary Stories about Men”, 1928, Leonov). I. Kataev (1902-1939) made his mark with stories and stories: “Heart” (1926), “Milk” (1930); A.P. Platonov (1899-1951): “Epiphanian Gateways” (1927).

In the poetry of the second half of the 20s, poems by V.V. stand out. Mayakovsky, S.A. Yesenina, E.G. Bagritsky (1895-1934), N.A. Aseeva (1889-1963), B.L. Pasternak, I.L. Selvinsky (1899-1968).

The remnants of capitalism in the minds of people are characteristic targets of satire of the 20s, the most significant achievements of which are associated with the names of Mayakovsky (poems “Pillar”, “Slicker”, etc., plays - “Bedbug”, 1928, “Bathhouse”, 1929), M. M. Zoshchenko (1895-1958) (collections of stories “Raznotyk”, 1923, “Dear Citizens”, 1926, etc.), I.A. Ilf (1897-1937) and E.P. Petrov (1903-1942) (novel “The Twelve Chairs”, 1928), A.I. Bezymensky (1898-1973) (play “The Shot”, 1930).

During these years, significant works were created both within the framework of the dominant movement (“socialist realism”) and outside it (many works of the second type became known much later): “Quiet Don” and the first part of “Virgin Soil Upturned” by M.A. Sholokhov, “The Master and Margarita” by M.N. Bulgakov, poems by A.A. Akhmatova, P.N. Vasilyeva, N.A. Klyueva, M.I. Tsvetaeva, novels and stories by A.M. Gorky, A.N. Tolstoy, N.A. Ostrovsky.

The focus of the literature of the 30s is a new person who grew up in Soviet reality.

The image of a young communist who selflessly devotes his strength and life to the cause of the revolution was created in the novel by N.A. Ostrovsky (1904-1936) “How the Steel Was Tempered” (1932-1934) - a vivid human document with enormous impact. A.S. Makarenko (1888-1939) in his “Pedagogical Poem” showed the labor re-education of street children, who for the first time felt their responsibility for a common cause.

The 20-30s were the heyday of Soviet children's literature. Her greatest achievements were fairy tales and poems by K.I. Chukovsky (1882-1969) and S.Ya. Marshak (1887-1964).

The art of theater did not stand still either. By decree of the Council of People's Commissars (1917), theaters were transferred to the jurisdiction of the People's Commissariat of Education. In 1919, signed by V.I. Lenin Decree of the Council of People's Commissars on the unification of the theatrical business, which proclaimed the nationalization of the theater.

The oldest Russian theaters took the first steps towards rapprochement with the new, working audience, rethinking the classics - interpreting them in some cases in terms of “consonance with the revolution.”

The development of the theater of this time was greatly influenced by the activities of a whole galaxy of talented directors: K.S. Stanislavsky, V.I. Nemirovich-Danchenko, V.E. Meyerhold, E.B. Vakhtangov, A.Ya. Tairova, A.D. Popova, K.A. Marjanishvili, G.P. Yura.

In the 30s, the first successes were achieved in creating a Soviet opera: “Quiet Don” by I.I. Dzerzhinsky (1935), “Into the Storm” by T.N. Khrennikov (1939, second edition 1952) “Semyon Kotko” by S. Prokofiev (1939).

A.N. contributed to the development of chamber vocal and instrumental music. Alexandrov, N.Ya. Myaskovsky, S.S. Prokofiev, G.V. Sviridov, Yu.A. Shaporin, V.Ya. Shebalin, D.D. Shostakovich, B.N. Tchaikovsky, B.I. Tishchenko, V.A. Gavrilin and others.

Soviet ballet experienced a radical renewal. Following the traditions of Tchaikovsky, Glazunov, Stravinsky, in this genre, Soviet composers established the importance of music as the most important, defining element of choreographic dramaturgy. Gorsky, who led the Bolshoi Theater troupe until 1922, staged classics (“The Nutcracker”, 1919) and new performances (“Stenka Razin” by A.K. Glazunov, 1918; “Eternally Living Flowers” to the music of B.F. Asafiev, 1922 , and etc.).

In the fine arts during this period, artists of numerous movements, schools and groups that arose at the end of the 19th century, in the turn of the century, continued their search.

The Institute of Artistic Culture (INHUK) in Moscow was significantly influenced by the ideas of V. Kandinsky. These two associations brought together the search for a perfect plastic form that corresponds to a sublime spiritual idea, the desire to theoretically comprehend artistic practice, to comprehend its laws and logic. In both institutes, a lot of work was done by both artists and art historians.

Artists V.M. Konashevich, B.M. Kustodiev, V.V. Lebedev and others took an active part in the work on illustrating the mass public library. N.A. worked on portraits of revolutionary figures and creative intelligentsia. Andreev, G.S. Vereisky, B.M. Kustodiev, P.Ya. Pavlikov. In landscape graphics by A.I. Kravchenko, N.I. Piskareva, V.D. Falileev's works were dominated by associative forms and motifs of raging elements. Specific images were created less frequently: woodcut "Armored Car" by N.N. Kupreyanov, linocut “Revolutionary Troops” by V.D. Falileeva.

list of used literature

1. Current problems of culture of the 20th century. M.: Nauka, 2013. - 286 p.

2. Galin S.A. Domestic culture of the 20th century. M.: UNITY-DANA, 2013. - 479 p.

3. Georgieva T.S. Russian culture: history and modernity. M.: Yurayt, 2012. - 576 p.

4. Mezhuev V.N. Current problems of cultural theory. M.: Mysl, 2013. - 364 p.

5. Sinyavsky A.D. Essays on Russian culture. M.: Progress, 2012. - 426 p.

Posted on Allbest.ru

Similar documents

Creation of the “three red banners” course based on the ideology of Maoism. Brief biography of Mao Zedong. Carrying out theater reform, the outrages of the Red Guards and the repression of the intelligentsia. Infringement of the economic interests of workers. Results of the "cultural revolution".

course work, added 11/22/2012

Consideration of the prerequisites for the “cultural revolution” in China. Politics of Mao Zedong; Red Guard movement. Strengthening the power of the “pragmatists” and weakening the position of Mao. Study of the socio-economic and political essence of the “cultural revolution”.

thesis, added 10/06/2014

History of the formation of the Soviet Union. The essence of the introduced V.I. Lenin's term "cultural revolution". Implementation of the Marxist-Leninist doctrine of the remaking of man. The main tasks of the cultural revolution. Features of the development of literature.

presentation, added 05/12/2015

Events of Russian history of the mid-14th century. Ivan the Terrible and the strengthening of the centralized state. Reforms and oprichnina. Achievements and contradictions in the cultural life of the country in the 1920-1930s. Differences in the creative positions of cultural figures.

test, added 06/16/2010

Analysis of the chronological framework, tasks of the cultural revolution and methods of their implementation. Characteristics of the essence of the authoritarian-bureaucratic style of party leadership in the field of science and art. Studying the concept of “Russian diaspora”, its main centers.

test, added 04/28/2010

The October Socialist Revolution as a natural result of the development of the world historical process, its objective and subjective prerequisites and necessity. Lenin's plan for the transition from a bourgeois-democratic revolution to a socialist one.

abstract, added 11/25/2009

Cultural construction of Belarus after October 1917. Creation of an education system and higher school in Soviet Belarus. Achievements and contradictions of national cultural policy in 1920-1940. Various phenomena of social life of society.

abstract, added 03/15/2014

The essence of the cultural revolution and its place in the development of socialist ideas and the transformation of society. Authoritarian-bureaucratic style of party leadership in the field of science, art and culture. The concept of Russian abroad, Russian literature in emigration.

test, added 11/28/2009

Causes of the deep crisis of culture in the 90s of the twentieth century. New trends in cultural life during the period of perestroika. School reform 1980-90 Manifestations of the crisis in fundamental and applied science. Artistic and spiritual life of the country in the 80-90s.

abstract, added 04/28/2010

The formation of a new type of culture as part of the construction of a socialist society, an increase in the share of people from the proletarian classes in the social composition of the intelligentsia. "Cultural revolution" in Russia. Morality in line with solving the problems of communism.

Cultural revolution in the USSR during the years

The main goal of the cultural transformation carried out by the Bolsheviks in the 1920s and 1930s was the subordination of science and art to Marxist ideology. A huge undertaking for Russia was the elimination of illiteracy (educational program). A unified state system of public education was created, and a Soviet school of several levels arose. In the 1st Five-Year Plan, compulsory four-year education was introduced, and in the 2nd Five-Year Plan, seven-year education was introduced. Universities and technical schools were opened, workers' faculties (faculties for preparing workers for entry into higher and secondary educational institutions) were closed. The training was ideological in nature. A new, Soviet intelligentsia was formed, but the Bolshevik government treated the old intelligentsia with suspicion.

In literature and art, the method of “socialist realism” was introduced, glorifying the party, its leader, and the heroics of the revolution. Among the writers were A. N. Tolstooy, M. A. Sholokhov, A. A. Fadeev, A. T. Tvardovskiy. The most important phenomena in musical life were the works of S. S. Prokofiev (music for the film “Alexander Nevsky”), A. I. Khachaturian (music for the film “Masquerade”), D. D. Shostakovich (opera “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk”, banned in 1936 for formalism). The songs of I. Dunaevsky, A. Alexandrov, V. Solovyov-Sedoy gained wide popularity. Cinematography has taken a significant step in its development. The most outstanding sculptural work of the 1930s. became the monument to V. Mukhinoa “Worker and Collective Farm Woman”. Through various creative unions, the state directed and controlled all the activities of the creative intelligentsia.

Socialist realism was recognized as the only artistic method, the principles of which were first formulated in the “Charter of the Writers' Union of the USSR” (1934). The main postulate of socialist realism was party identity, socialist ideology. The aesthetic concept of “realism” was voluntarily combined with the political definition of “socialist”, which in practice led to the subordination of literature and art to the principles of ideology and politics, to the emasculation of the very content of art. Socialist realism was a universal method prescribed, in addition to literature, music, cinema, fine art art and even ballet. An entire era in Russian culture passed under his flag. Many artists whose work did not fit into the Procrustean bed of socialist realism were, at best, excommunicated from literature and art, and at worst, subjected to repression (Mandelshtam, Meooyerhold, Pilnyak, Babel, Kharms, Pavel Vasiliev, etc.). Socialist realism

In 1918, the implementation of Lenin's plan for monumental propaganda began. In accordance with this plan, monuments were removed that, in the opinion of the new government, did not represent historical or artistic value, for example, monuments to Alexander III in St. Petersburg and General Skobelev in Moscow. At the same time, monuments (busts, figures, steles, memorial plaques) began to be created to the heroes of the revolution, public figures, writers, and artists. The new monuments were supposed to make the ideas of socialism visually clear. Both famous masters (S.T. Konenkov, N.A. Andreev) and young sculptors of different schools and directions, including students of art schools, were involved in the work. In total, 25 monuments were erected in Moscow over the years, and 15 in Petrograd. Many monuments did not survive, mainly because they were made of temporary materials (plaster, concrete, wood). Sculpture

In Petrograd, over the years, a monument to the “Fighters of the Revolution” was created - the Field of Mars. Project by architect L.V. Rudneva.

Obelisk in honor of the first Soviet Constitution in Moscow. Concrete Not preserved. Architect D. N. Osipov.

Sculptural group "Worker and Collective Farm Woman". They hold in their outstretched hands a sickle and a hammer, which make up the coat of arms of the Soviet Union. The author of this work is V.I. Mukhina, a major sculptor of this era, one of the most famous women in the country.

Architecture The leading direction in architecture in the 1920s was constructivism, which sought to use new technology to create simple, logical, functionally justified forms that were appropriate for design. Techniques characteristic of constructivism are the combination of solid flat walls with large glazed surfaces, the combination of volumes of different compositions. Soviet constructivism is represented in the works of V.E. Tatlin. He tried to use a wide variety of materials to construct his technical structures, including wire, glass and sheet metal. The scope of club construction can be judged by the fact that 480 clubs were built in the country in just one year, including 66 in Moscow. A whole series of architecturally original clubs were built during this period according to the designs of the architect K.S. Melnikov in Moscow and the Moscow region.

Club named after Rusakov in Sokolniki (years)

Palace of Culture named after Likhachev, created according to the design of the largest Soviet masters brothers L.A., V.A., A.A. Vesnin.

Painting and graphics In the 20s, the most mobile, efficient and widespread type of fine art was graphics: magazine and newspaper drawings, posters. They responded most quickly to the events of the time due to their brevity and clarity. During these years, two types of posters, heroic and satirical, developed, the most prominent representatives of which were Moore and Denis. Moor (D.S. Orlov) owned political posters that became classic Soviet graphics “Have you signed up as a volunteer?” (1920), "Help!" (). Posters by Denis (V.N. Denisov) are built on a different principle. They are satirical, accompanied by poetic texts, and the influence of popular popular print is noticeable in them. Denis also widely uses the technique of caricature portraits. He is the author of such famous posters as “Either death to capital, or death under the heel of capital” (1919), “World-eating fist” (1921).

Moor (D.S. Orlov) “Have you signed up as a volunteer?” (1920), "Help!" ().

Denis (V.N. Denisov) “Either death to capital, or death under the heel of capital” (1919), “World-Eating Fist” (1921).

In the post-revolutionary years, a completely innovative form of propaganda art appeared - “Windows of ROSTA” (Russian telegraph agency), in which M.M. Cheremnykh, V.V. Mayakovskiy, Moor played a special role. The posters, accompanied by sharp text, responded to the most pressing issues of the day: they called for the defense of the country, called for deserters, and campaigned for something new in everyday life. They were posted in storefronts or shop windows, in clubs, and at train stations. "Windows of ROSTA" had a great influence on the timeline of the Great Patriotic War.

In addition to graphics, the basic forms of painting also developed in the 1960s. In the visual arts during these years there were different directions. The art of the Russian avant-garde not only continued to develop, but also experienced a true flowering. The time of revolutionary transformation attracted artists to new creative experiments. Avant-garde movements such as cubism, futurism, and abstractionism became widespread in Russia. The largest representatives of the Russian avant-garde are M.3. Chagall, N.S. Goncharova, K.S. Malevich, V.V. Kandinsky, M.F. Larionov, A.V. Lentulov, P.N. Filonov. Avant-gardists were intolerant of representatives of classical art and considered themselves revolutionary artists creating new proletarian art. They controlled many of the printing presses and exhibition spaces.